Recently I read a brilliant post which points out a lot of the myths surrounding autism. Luckily it also provides the facts. If you're interested, please pop on over to Let's Chat Autism but do come back!

There was one section which interested me greatly:

Myth: Autism spectrum disorders are something to be hidden. Other

students should not know about the presence of an ASD in a classmate. If

you do not tell the other children, they will not know that something

is “wrong” with the student with an ASD.

Fact: Students need to know when their classmates have a developmental

disability that is likely to effect interactions and learning. Students

as young as five years old are able to identify differences in their

peers. When students are not given appropriate information, they are

likely to draw the wrong conclusions, based on their very limited

experiences. Confidentiality rules must be taken into consideration and

parental approval sought to teach peers how to understand and interact

successfully with children with ASD.

From the start of our journey, I always knew I wanted to 'tell' people about Sasha. This was driven by a desire to build awareness, and to help others understand. It's only a hidden disability for as long as we try to keep it hidden.

Sasha's speech didn't develop at the same rate as her peers - at this stage she has a great vocabulary, but an unusual turn of phrase, and her sounds are still not totally clear. That makes it obvious that there is something 'different' about her. I'll have to be honest and say that sometimes, when she does say something in public which is not quite right, my heart does sink a little. Simply because I realise how it sets her apart from her classmates and it reminds me of the gap. Most of the time it also makes me smile, because she really is infectious.

Along

the way, I've met other mums of children with autism who haven't wanted

anyone to know about their child's diagnosis. They have had their own

individual reasons for not wanting to 'share', and the reasons could

have been anything from the personality of the parent, to the child not

being 'very' autistic - i.e. the parents have felt that it is not that

noticeable and therefore they don't want to draw attention to the

'difference'. I have explained before that I almost feel a strange sense of relief that Sasha's speech makes her 'noticeable' - maybe not instantly, but certainly after spending any length of time with her. It must be so much harder when people question a diagnosis even more than they did for us. 'She's fine' or 'she'll grow out of it' were probably two of the most difficult things to hear when Sasha was younger, however well-intentioned.

Over the past 2 years there have been times when I have questioned whether I should have been so open and honest about Sasha's diagnosis. I think there have been times when others have hinted indirectly that it was the wrong thing to do. I still stand by my decision; it's not in my nature to be secretive. Good friends have told me both that they think I'm brave, but also that they believe, like me, that it's the right thing to do.

Being open leads to its own problems though. Now Sasha is 5, and in Year 1, I've been wondering at what point we need to explain to her peers why she is unable to follow instructions in the same way as they do, and why she can 'get away with' not joining in. Her classmates don't know what makes Sasha different, but how can they even begin to understand if we don't tell them? The difficulty is though, if we do tell them, how do we tell Sasha?

She is still really unaware of her own difficulties, and the consequences of refusing to participate. Some of her classmates are already very aware of Sasha. Luckily they seem to just love her for who she is right now, which is heart-warming of course. If we try to explain autism (!) to her classmates, there's every chance one of them would give her the story at some point in the not-too-distant future. Or maybe even half the story. And she might just understand a quarter of it. See what that might lead to?! Dangerous territory I fear.

Sadly this is the scenario we will face at some point. Explaining to Sasha is probably going to be the most difficult thing to do, ever. How will I know when it's the right time? Will there ever be a right time?

Being bullied is a sad truth for lots of children with autism. For lots of children without, too. I can honestly say I never felt the fear of being a victim of bullying thankfully - bitchiness which happens with girls, yes, but not bullying. That doesn't mean I can't imagine the despair of it. There are bullies everywhere in the world and sadly they do tend to pick on the weaker ones. Of course the children now are too young, but we have to face the fact that it is likely to happen in the future.

In the meantime I'm obviously keen to pave as smooth a path as possible for Sasha. If we educate more parents and children about autism, then hopefully there will be less bullying and more understanding.

Sign up for FREE emails!

Featured post

PDA in the Family: Life After the Lightbulb Moment Book

Our book, PDA in the Family: Life After the Lightbulb Moment, is out now! We wanted to help other people understand more about Pathological ...

Popular Posts

-

Our fifteen year old daughter is autistic. She was diagnosed with Autism at the age of two and a half. This blog began the day aut...

-

What is the difference between ODD (Oppositional Defiant Disorder) and PDA (Pathological Demand Avoidance)? This is a question I have been a...

-

'What is PDA, or Pathological Demand Avoidance ?' and 'does my child have PDA?' are questions being asked by more and more p...

-

Pathological Demand Avoidance is best understood as a profile of autism, characterised by extremely high levels of anxiety. PDA childre...

-

One of my favourite books of all time is the New York Times Bestseller, Wonder by R.J.Palacio. It's a story of a young boy called August...

-

I'm often asked about which strategies can help children with Pathological Demand Avoidance in a school setting. I do know that many str...

-

Huge, enormous, massive, gigantic, humongous, GIANT homemade bubbles. Here's a great activity which will make your children very happy t...

-

Following on from my last blog post discussing whether Pathological Demand Avoidance is real , I'm going to take a look at another quest...

-

Time flies, as the saying goes, and I can hardly believe it's been nearly six years since I wrote a post on this blog titled ' Strat...

-

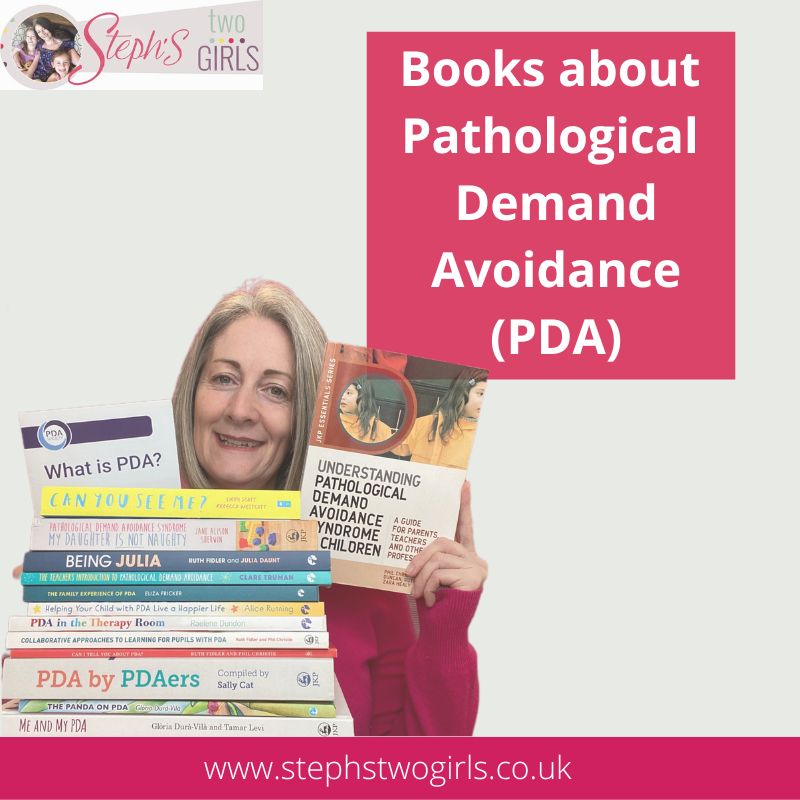

There are now several published books on Pathological Demand Avoidance , a profile of autism often referred to as PDA. Many of these have p...

Like us

'Autism is a spectrum condition and affects people in different ways. Like all people, autistic people have their own strengths and weaknesses. Social interaction and communication can be difficult for some autistic people but others may enjoy it. Intense interests and repetitive behaviour are often seen along with differing sensory experiences'.

What is PDA (Pathological Demand Avoidance)?

What is PDA (Pathological Demand Avoidance)?

Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) is a profile of Autism. The central difficulty for people with PDA is their avoidance of the everyday demands made by other people, due to their high anxiety levels when they feel that they are not in control.

Children may sometimes be described as having 'challenging' or 'oppositional' behaviour. Parents describe life as 'walking on eggshells'.

Blog Archive

-

▼

2012

(85)

-

▼

November

(12)

- 12 Days of Christmas Toy Reviews - Part 2.

- 12 Days of Christmas Toy Reviews - Part 1.

- Chance to win one of those cute little fruity thin...

- Saturday is Caption Day - my first ever!

- Speech and Chatting With Children by I CAN

- Autism and Mainstream Schooling - Yes!

- Mummy 'Me' Time and cakes. A good mix (ho ho).

- Diary of a 7 year old - all the important things c...

- Autism: How and when to educate others?

- Autism and mainstream schooling - do they really mix?

- Moshi HQ - we love Moshi Monsters!!

- Sylvanian Families: A Study in Art Exhibition - On...

-

▼

November

(12)

©Copyrights 2011-2021 Sora Templates