We've certainly experienced similar situations and thought processes that this family went through ourselves. With PDA, there is no amount of cajoling which works to smooth things over, and no rewards which work to make life easier. The meltdowns can be explosive and violent, or drawn out tensely in a ball of anxiety and helplessness, but they have the same effect in terms of the aftermath. The challenges don't disappear and can't be easily forgotten about or brushed under the carpet. Holidays can end up being even more about the feeling of treading on eggshells than everyday life at home is. And as that realisation dawns, parents often begin to question whether it's worth having holidays at all.

**********

Part 1: The element of surprise (or, how we royally screwed things up)

Jack has always responded well to novelty and surprises, in the way that I have read many PDAers do. In the past, we’ve kept him safely in the dark about trips and events we knew he would like, but that would undoubtedly cause him anxiety if he had time to dwell on them. So, that’s how we planned our post-lockdown holiday to Butlins, home of good old-fashioned family fun. Bring it on!

Originally the plan was a very short camping break to a local holiday park in an attempt to ‘save some money’ (hmmm, ok then). But, as D-day drew closer, and the weather became more unpredictable (and our weariness from dealing with a world heavyweight champion PDAer over lockdown really set-in) we

decided to do what we do best: Throw Money At It. Yes we would spontaneously and recklessly throw money – money that we don’t have, mind you – at the situation, and go somewhere where we wouldn’t have to sleep, argue or urinate in the open air and pretend it was fun.

We knew Jack would fixate, obsess, attempt to control the new trip and even possibly refuse it so we took what we thought was the sensible decision to keep the details from him until we arrived at Butlins. He’d been to another Butlins three years go and thoroughly enjoyed it. So we were GUARANTEED he’d love it now, right? (In hindsight, his PDA was heavily under wraps at the point of the first Butlins trip, a combination of him masking and us assuming he was ‘young for his age’ and ‘highly strung’. Those old chestnuts.) But we didn’t let this annoying thought trouble us as we merrily entered the holiday park, or The Jaws of Doom as I soon came to refer to it.

Part 2: Yep, we should have gone camping.

Let’s fast-forward four hours, to the ladies’ toilets of the on-site restaurant, where Jack has locked himself in a cubicle and is hammering on the walls with hands and feet, unravelling toilet paper and trying to break the dispenser off the wall. He’s gone full ‘red’, as we call it, and the panic attack is in full swing. A tiny, blond three year old in the next cubicle is trying to do a wee, but her seat is shaking and the walls are vibrating and she begins to cry.

We’d had Meltdown Phase One earlier on, when he had become angry and unable to walk after getting upset that the fairground wasn’t up to scratch, and I had to give him a piggyback all the way to the hotel. No mean feat when your nearly-nine year old is only 1.5 stone lighter than you. But it’s surprising what transpires when your child strikes the fear of God in to you in public. I like to think of it as the ‘containment’ phase of dealing with the behaviour, which roughly translates to ‘do what the hell he wants and hope it passes’.

Anyway, back to the toilet. By the time my other half Sam arrived, pushing past the bemused mums, Jack had opened the cubicle door and melted in to a soggy mess on the floor. Ear defenders were applied, as was my jacket over his head, and during this brief lull Sam carried/hauled him outside. Jack’s abject fear, embarrassment, panic, anxiety – all of those raw and painful emotions – were overflowing. I looked at Sam and in that moment, we silently agreed it was time to go home. Between us we carried Jack to the car, with fellow holidaymakers looking on uncomfortably. You know what it’s like, when people pretend not to look but they can’t help it. And then they glance down at their own offspring, as if to reassure themselves that’s it’s definitely NOT happening to them. Jack was now lying on the floor, begging to go home. ‘We sh-sh-should have g-g-gone camping mummy!’

Shell-shocked, realising the huge mistake we had made in taking the control away from him - and forcing him to undo all his expectations - was earth-shattering. We had been So Very Wrong. Home was where we would go. We shoehorned him in to the car, already calculating how long it would take to get back and working out what we’d do about returning for the luggage. Jack’s panic attack began to grow again, his arms flailed and my sunglasses flew across the car. Hand sanitiser was angrily dispensed all over the

seats, ripped tissues floated in the air and I narrowly missed a powerful punch. In desperation I waved my phone at him and shouted the magic words ‘YOUTUBE?’ and, like a switch flicking in the opposite direction, it was over.

Part 3 – The Butlins’ Black Hole (abandon hope all ye who enter here)

We didn’t go home. Jack decided we would stay - as long as he was allowed to go to the arcade as much as he liked and we of course agreed. Anything to try and salvage something from this shit-show, we thought.

Over the next three days, we had some tiny moments of uncomplicated fun: the amazing circus show which he actually wanted to see, the moment he won a ticket jackpot in the arcade, when he and Sam completed all levels of a zombie-shooting game and the evening Jack decided we were on a date and proceeded to kiss me full on the lips for as long as he could - making exaggerated ‘mwah’ sounds, which made me giggle, spill my wine and nearly fall off my chair (cue very strange looks for the tables around us). I took clear, mental pictures of these moments, as I knew they would soon fade from my memory, muddied by my anxiety and trauma.

The holiday (although ‘ordeal’ would be a more accurate word), was an uphill struggle of immense proportions. Lots of light switch violent meltdowns, flat-out refusals to move from the arcade and

anxious silences in our hotel room. Jack even refused to do things he liked, such as the water park, and only appeared happy and regulated in the bright and noisy arcade - ear defenders on - mesmerized by the lights, screens, colours and the chance of winning more and more tickets. Jack’s control of me reached new levels and some days I was not allowed to have a bath, eat when I wanted to or pop out for a walk. I of course accepted all of this willingly, knowing that to rail against it would not be worth the

outcome.

Sam and I should have been taking any good moment, however short-lived, and cherishing it. But we simply couldn’t. If Jack was calm, one or both of us would be a nervous, tightly-would wreck,

anticipating the next major issue and chucking in recriminations for good measure. Snappy, resentful, accusatory, emotional and just so very exhausted – we lived in a vacuum of negativity and mental

exhaustion. There was nothing left in the tank. We counted the days, and then the hours until we could return home.

Part 4 – The uncomfortable truth

I’d absolutely love to end this blog with a lighthearted ‘ah, but it wasn’t all bad, we were able to take away some happy memories’, and throw in an insta-perfect pic or two of us all looking suitably cute. But that wouldn’t be truthful of me and it would be insulting to those of you who live with PDA every day and know that sometimes, it’s best to just try and forget, move on and don’t look back. Yes, there ARE some beautiful, happy, funny moments in our life with Jack, but they didn’t happen on this holiday. It’s burnt our fingers when it comes planning future holidays, as we truly thought we were on to a winner with this one, and how wrong we were. Would things have been better if we had told him the truth about our destination? Probably. But really and truly, who knows. As you PDA parent experts know, one of a PDAers’ superpowers is unpredictability.

For now, we’re glad to be home in our low-demand bubble, where we don’t feel eyes of the world upon us. Getting through each day in any way we can.

**********

Thanks for taking the time to read. Comments are much appreciated and sharing on social media could really help put these posts in front of people who have still not heard about PDA.

For more reading about what Pathological Demand Avoidance is, please see 'Challenging Behaviour and PDA', and for an idea of how to help please read Strategies For PDA.

There's a chance PDA can be misdiagnosed as ODD (Oppositional Defiant Disorder) but there is a distinct difference. More information is in my post titled the difference between PDA and ODD.

A variety of experiences of living with PDA can be read in the Our PDA story series.

If you feel up to sharing your own experiences with my readers to help spread understanding (this can be anonymously), please email stephstwogirls@gmail.com.

The PDA Society website has lots of information about Pathological Demand Avoidance.

To find out more about our experiences, please check out our 'About Us' page. If you are looking for more information on Pathological Demand Avoidance, the posts below may help.

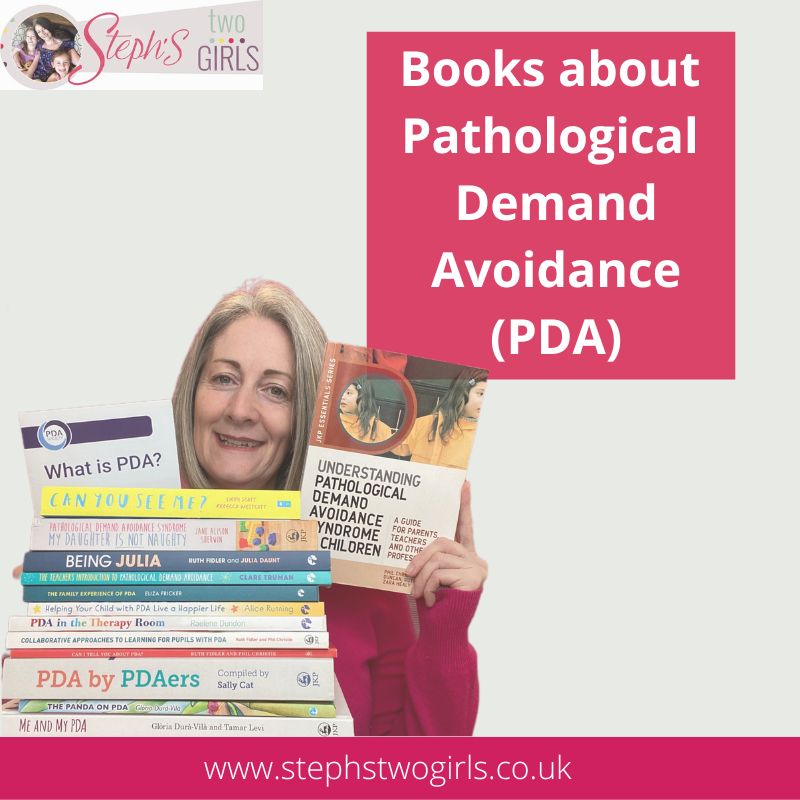

Books about the Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) profile of autism

What is PDA (Pathological Demand Avoidance)?

Ten things you need to know about Pathological Demand Avoidance

Does my child have Pathological Demand Avoidance?

The difference between PDA and ODD

Strategies for PDA (Pathological Demand Avoidance)

Pathological Demand Avoidance: Strategies for Schools

Challenging Behaviour and PDA

Is Pathological Demand Avoidance real?

Autism with demand avoidance or Pathological Demand Avoidance?

To follow me on other social media channels, you can find me at the following links or click the icons below!

Facebook: www.facebook.com/stephstwogirls

Twitter: twitter.com/stephstwogirls

YouTube: www.youtube.com/c/stephcurtis

Instagram: www.instagram.com/stephstwogirls/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are always very much appreciated and can really help the conversation go further...